Chronic kidney disease

Kidney failure - chronic; Renal failure - chronic; Chronic renal insufficiency; Chronic kidney failure; Chronic renal failureChronic kidney disease is the slow loss of kidney function over time. The main job of the kidneys is to remove wastes and excess water from the body.

Causes

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) slowly gets worse over months or years. You may not notice any symptoms for some time. The loss of function may be so slow that you do not have symptoms until your kidneys have almost stopped working.

The final stage of CKD is called end-stage renal disease (ESRD). At this stage, the kidneys are no longer able to remove enough wastes and excess fluids from the body. At this point, you would need dialysis or a kidney transplant.

End-stage renal disease

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is the last stage of long-term (chronic) kidney disease. This is when your kidneys can no longer support your body's...

Kidney transplant

A kidney transplant is surgery to place a healthy kidney into a person with kidney failure.

Diabetes and high blood pressure are the 2 most common causes and account for most cases.

Diabetes

Diabetes is a long-term (chronic) disease in which the body cannot regulate the amount of sugar in the blood.

High blood pressure

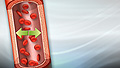

Blood pressure is a measurement of the force exerted against the walls of your arteries as your heart pumps blood to your body. Hypertension is the ...

Many other diseases and conditions can damage the kidneys, including:

- Autoimmune disorders (such as systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma)

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease. In this disease, the immune system of the body mistakenly attacks healthy tissue. It c...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleScleroderma

Scleroderma is a disease that involves the buildup of fibrous tissue in the skin and elsewhere in the body. It also damages the cells that line the ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Birth defects of the kidneys (such as polycystic kidney disease)

Polycystic kidney disease

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a kidney disorder passed down through families. In this disease, many cysts form in the kidneys, causing them to ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Some toxic chemicals

- Injury to the kidney

-

Kidney stones and infection

Kidney stones

A kidney stone is a solid mass made up of tiny crystals. One or more stones can be in the kidney or ureter at the same time.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Problems with the arteries feeding the kidneys

- Some medicines, such as antibiotics, and pain and cancer medicines

- Backward flow of urine into the kidneys (reflux nephropathy)

Reflux nephropathy

Reflux nephropathy is a condition in which the kidneys are damaged by the backward flow of urine into the kidney.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

CKD leads to a buildup of fluid and waste products in the body. This condition affects most body systems and functions, including:

- High blood pressure

- Low blood cell count

- Vitamin D and bone health

Symptoms

The early symptoms of CKD are the same as for many other illnesses. These symptoms may be the only sign of a problem in the early stages.

Symptoms may include:

- Appetite loss

-

General ill feeling and fatigue

General ill feeling

Malaise is a general feeling of discomfort, illness, or lack of well-being.

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleFatigue

Fatigue is a feeling of weariness, tiredness, or lack of energy.

Read Article Now Book Mark Article -

Headaches

Headaches

A headache is pain or discomfort in the head, scalp, or neck. Serious causes of headaches are rare. Most people with headaches can feel much better...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Itching (pruritus) and dry skin

Pruritus)

Itching is a tingling or irritation of the skin that makes you want to scratch the area. Itching may occur all over the body or only in one location...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Nausea

Nausea

Nausea is feeling an urge to vomit. It is often called "being sick to your stomach. "Vomiting or throwing-up forces the contents of the stomach up t...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Weight loss without trying to lose weight

Weight loss

Unexplained weight loss is a decrease in body weight, when you did not try to lose the weight on your own. Many people gain and lose weight. Uninten...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article

Symptoms that may occur when kidney function has gotten worse include:

-

Abnormally dark or light skin

Abnormally dark or light skin

Abnormally dark or light skin is skin that has turned darker or lighter than normal.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Bone pain

-

Drowsiness or problems concentrating or thinking

Drowsiness

Drowsiness refers to feeling more sleepy than normal during the day. People who are drowsy may fall asleep when they do not want to or at times whic...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Numbness in the hands and feet

Numbness

Numbness and tingling are abnormal sensations that can occur anywhere in your body, but they are often felt in your fingers, hands, feet, arms, or le...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Muscle twitching or cramps

Muscle twitching

Muscle twitches are fine movements of a small area of muscle.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Breath odor

Breath odor

Breath odor is the scent of the air you breathe out of your mouth. Unpleasant breath odor is commonly called bad breath.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Easy bruising, or blood in the stool

Bruising

Bleeding into the skin can occur from broken blood vessels that form tiny red dots (called petechiae). Blood also can collect under the tissue in la...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Excessive thirst

Excessive thirst

Excessive thirst is an abnormal feeling of always needing to drink fluids.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Frequent hiccups

Hiccups

A hiccup is an unintentional movement (spasm) of the diaphragm, the muscle at the base of the lungs. The spasm is followed by quick closing of the v...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Problems with sexual function

- Menstrual periods stop (amenorrhea)

Amenorrhea

Absence of a woman's monthly menstrual period is called amenorrhea. Primary amenorrhea is when a girl has not yet started her monthly periods, and sh...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Shortness of breath

- Sleep problems

- Swelling in the hands and feet

-

Vomiting

Vomiting

Nausea is feeling an urge to vomit. It is often called "being sick to your stomach. "Vomiting or throwing-up forces the contents of the stomach up t...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Exams and Tests

Most people will have high blood pressure at all stages of CKD. During an exam, your health care provider may also hear abnormal heart or lung sounds in your chest. You may have signs of nerve damage during a nervous system exam.

A urinalysis may show protein or other changes in your urine. These changes may appear months to years before symptoms appear.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is the physical, chemical, and microscopic examination of urine. It involves a number of tests to detect and measure various compounds th...

Protein

Proteins are the building blocks of life. Every cell in the human body contains protein. The basic structure of protein is a chain of amino acids. ...

Tests that check how well the kidneys are working include:

-

Creatinine clearance

Creatinine clearance

The creatinine clearance test helps provide information about how well the kidneys are working. The test compares the creatinine level in urine with...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Creatinine levels

Creatinine

The creatinine blood test measures the level of creatinine in the blood. This test is done to see how well your kidneys are working. Creatinine in t...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

BUN

BUN stands for blood urea nitrogen. Urea nitrogen is what forms when protein breaks down. A test can be done to measure the amount of urea nitrogen ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

CKD changes the results of several other tests. You may need to have the following blood tests as often as every 2 to 3 months when kidney disease gets worse:

-

Albumin

Albumin

Albumin is a protein made by the liver. A serum albumin test measures the amount of this protein in the clear liquid portion of the blood. Albumin c...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Calcium

Calcium

The calcium blood test measures the level of calcium in the blood. This article discusses the test to measure the total amount of calcium in your blo...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Cholesterol

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a soft, wax-like substance found in all parts of the body. Your body needs a little bit of cholesterol to work properly. But too muc...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Complete blood count (CBC)

Complete blood count

A complete blood count (CBC) test measures the following:The number of white blood cells (WBC count)The number of red blood cells (RBC count)The numb...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Electrolytes

Electrolytes

Electrolytes are minerals in your blood and other body fluids that carry an electric charge. Electrolytes affect how your body functions in many ways...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article -

Magnesium

Magnesium

A serum magnesium test measures the level of magnesium in the blood.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Phosphorous

Phosphorous

The phosphorus blood test measures the amount of phosphate in the blood.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Potassium

Potassium

This test measures the amount of potassium in the fluid portion (serum) of the blood. Potassium (K+) helps nerves and muscles communicate. It also ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Sodium

Sodium

The sodium blood test measures the concentration of sodium in the blood. Sodium can also be measured using a urine test.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Other tests that may be done to look for the cause or type of kidney disease include:

-

CT scan of the abdomen

CT scan of the abdomen

An abdominal CT scan is an imaging method. This test uses x-rays to create cross-sectional pictures of the belly area. CT stands for computed tomog...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

MRI of the abdomen

MRI of the abdomen

An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging scan is an imaging test that uses powerful magnets and radio waves. The waves create pictures of the inside ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Ultrasound of the abdomen

Ultrasound of the abdomen

Abdominal ultrasound is a type of imaging test. It is used to look at organs in the abdomen, including the liver, gallbladder, spleen, pancreas, and...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Kidney biopsy

Kidney biopsy

A kidney biopsy is the removal of a small piece of kidney tissue for examination.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Kidney scan

Kidney scan

A renal scan is a nuclear medicine exam in which a small amount of radioactive material (radioisotope) is used to measure the function of the kidneys...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Kidney ultrasound

- Urine protein

This disease may also change the results of the following tests:

-

Erythropoietin

Erythropoietin

The erythropoietin test measures the amount of a hormone called erythropoietin (EPO) in blood. The hormone tells stem cells in the bone marrow to mak...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Parathyroid hormone (PTH)

PTH

The PTH test measures the level of parathyroid hormone in the blood. PTH stands for parathyroid hormone. It is a protein hormone released by the par...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article -

Bone density test

Bone density test

A bone mineral density (BMD) test measures how much calcium and other types of minerals are in an area of your bone. This test helps your health care...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Vitamin D level

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin. Fat-soluble vitamins are stored in the body's fatty tissue and liver.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Treatment

Blood pressure control will slow further kidney damage.

Blood pressure control

Hypertension is another term used to describe high blood pressure. High blood pressure can lead to: StrokeHeart attackHeart failureKidney diseaseEar...

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are used most often.

- The goal is to keep blood pressure at or below 130/80 mm Hg.

Making lifestyle changes can help protect the kidneys, and prevent heart disease and stroke, such as:

Heart disease

Coronary heart disease is a narrowing of the blood vessels that supply blood and oxygen to the heart. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is also called co...

Stroke

A stroke occurs when blood flow to a part of the brain stops. A stroke is sometimes called a "brain attack. " If blood flow is cut off for longer th...

- DO NOT smoke.

- Eat meals that are low in fat and cholesterol.

- Get regular exercise (talk to your provider or nurse before starting to exercise).

- Take medicines to lower your cholesterol, if needed.

Lower your cholesterol

Your body needs cholesterol to work properly. But extra cholesterol in your blood causes deposits to build up on the inside walls of your blood vess...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Keep your blood sugar under control.

Blood sugar

When you have diabetes, you should have good control of your blood sugar (glucose). If your blood sugar is not controlled, serious health problems c...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Avoid eating too much salt or potassium.

Salt

Too much sodium in your diet can be bad for you. If you have high blood pressure or heart failure, you may be asked to limit the amount of salt (whi...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Always talk to your provider before taking any over-the-counter medicine. This includes vitamins, herbs and supplements. Make sure all of the providers you visit know you have CKD. Other treatments may include:

Vitamins

Vitamins are a group of substances that are needed for normal cell function, growth, and development. There are 13 essential vitamins. This means th...

- Medicines called phosphate binders, to help prevent high phosphorous levels

- Extra iron in the diet, iron pills, iron given through a vein (intravenous iron) special shots of a medicine called erythropoietin, and blood transfusions to treat anemia

Anemia

Anemia is a condition in which the body does not have enough healthy red blood cells. Red blood cells provide oxygen to body tissues. Different type...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Extra calcium and vitamin D (always talk to your provider before taking)

Your provider may have you follow a special diet for CKD.

Diet for CKD

You may need to make changes to your diet when you have chronic kidney disease (CKD). These changes may include limiting fluids, eating a low-protei...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article- Limiting fluids

- Eating less protein

- Restricting phosphorous and other electrolytes

- Getting enough calories to prevent weight loss

All people with CKD should be up-to-date on the following vaccinations:

-

Hepatitis A vaccine

Hepatitis A vaccine

All content below is taken in its entirety from the CDC Hepatitis A Vaccine Information Statement (VIS): www. cdc. gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statement...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Hepatitis B vaccine

Hepatitis B vaccine

All content below is taken in its entirety from the CDC Hepatitis B Vaccine Information Statement (VIS): www. cdc. gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statement...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Flu vaccine

Flu vaccine

All content below is taken in its entirety from the CDC Inactivated Influenza Vaccine Information Statement (VIS) www. cdc. gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Pneumococcal vaccine (also called "pneumonia vaccine")

Pneumococcal vaccine

All content below is taken in its entirety from the CDC Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine Information Statement (VIS): www. cdc. gov/vaccines/hcp/v...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - COVID-19

Support Groups

More information and support for people with CKD and their families can be found at a kidney disease support group.

Kidney disease support group

The following organizations are good resources for information on kidney disease:American Geriatrics Society's Health in Aging Foundation -- www. hea...

Outlook (Prognosis)

Many people are not diagnosed with CKD until they have lost most of their kidney function.

There is no cure for CKD. Whether it worsens to ESRD, and how quickly, depends on:

ESRD

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is the last stage of long-term (chronic) kidney disease. This is when your kidneys can no longer support your body's...

- The cause of kidney damage

- How well you take care of yourself

Kidney failure is the last stage of CKD. This is when your kidneys can no longer support our body's needs.

Your provider will discuss dialysis with you before you need it. Dialysis removes waste from your blood when your kidneys can no longer do their job.

Dialysis

Dialysis treats end-stage kidney failure. It removes harmful substances from the blood when the kidneys cannot. This article focuses on peritoneal d...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleIn most cases, you will go to dialysis when you have only 10 to 15% of your kidney function left.

Even people who are waiting for a kidney transplant may need dialysis while waiting.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

-

Anemia

Anemia

Anemia is a condition in which the body does not have enough healthy red blood cells. Red blood cells provide oxygen to body tissues. Different type...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Bleeding from the stomach or intestines

- Bone, joint, and muscle pain

- Changes in blood sugar

- Damage to nerves of the legs and arms (peripheral neuropathy)

Peripheral neuropathy

Peripheral nerves carry information to and from the brain. They also carry signals in both directions between the spinal cord and the rest of the bo...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Dementia

Dementia

Dementia is a loss of brain function that occurs with certain diseases. It affects one or more brain functions such as memory, thinking, language, j...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Fluid buildup around the lungs (pleural effusion)

Pleural effusion

A pleural effusion is a buildup of fluid between the layers of tissue that line the lungs and chest cavity.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Heart and blood vessel complications

- High blood phosphorous levels

-

High blood potassium levels

High blood potassium levels

High potassium level is a problem in which the amount of potassium in the blood is higher than normal. The medical name of this condition is hyperka...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is a condition in which 1 or more of the parathyroid glands in your neck produce too much parathyroid hormone (PTH).

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Increased risk of infections

- Liver damage or failure

-

Malnutrition

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is the condition that occurs when your body does not get enough nutrients.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Miscarriages and infertility

Miscarriages

A miscarriage is the spontaneous loss of a fetus before the 20th week of pregnancy. Pregnancy losses after the 20th week are called stillbirths. Mi...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleInfertility

Infertility means you cannot get pregnant (conceive). There are 2 types of infertility:Primary infertility refers to couples who have not become preg...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Seizures

Seizures

A seizure is the physical changes in behavior that occurs during an episode of specific types of abnormal electrical activity in the brain. The term ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Swelling (edema)

Edema

Swelling is the enlargement of organs, skin, or other body parts. It is caused by a buildup of fluid in the tissues. The extra fluid can lead to a ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Weakening of the bones and increased risk of fractures

Prevention

Treating the condition that is causing the problem may help prevent or delay CKD. People who have diabetes should control their blood sugar and blood pressure levels and should not smoke.

References

Christov M, Sprague SM. Chronic kidney disease - mineral bone disorder. In: Yu ASL, Chertow GM, Luyckx VA, Marsden PA, Skorecki K, Taal MW, eds. Brenner and Rector's The Kidney. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 53.

Grams ME, McDonald SP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease and dialysis. In: Johnson RJ, Floege J, Tonelli M, eds. Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 80.

Levey AS, Sarnak MJ. Chronic kidney disease. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 116.

Taal MW. Classification and management of chronic kidney disease. In: Yu ASL, Chertow GM, Luyckx VA, Marsden PA, Skorecki K, Taal MW, eds. Brenner and Rector's The Kidney. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 59.

-

Urination

Animation

-

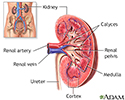

Kidney anatomy - illustration

The kidneys are responsible for removing wastes from the body, regulating electrolyte balance and blood pressure, and the stimulation of red blood cell production.

Kidney anatomy

illustration

-

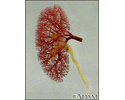

Kidney - blood and urine flow - illustration

This is the typical appearance of the blood vessels (vasculature) and urine flow pattern in the kidney. The blood vessels are shown in red and the urine flow pattern in yellow.

Kidney - blood and urine flow

illustration

-

Glomerulus and nephron - illustration

The kidneys remove excess fluid and waste from your body. Blood is filtered in the kidneys through nephrons. Each nephron contains a network of small blood vessels, called glomerulus, which are enclosed in a sac called Bowman's capsule. The filtered waste product (urine) flows through tiny tubes and is then passed from the kidneys to the bladder through bigger tubes called ureters.

Glomerulus and nephron

illustration

-

Kidney anatomy - illustration

The kidneys are responsible for removing wastes from the body, regulating electrolyte balance and blood pressure, and the stimulation of red blood cell production.

Kidney anatomy

illustration

-

Kidney - blood and urine flow - illustration

This is the typical appearance of the blood vessels (vasculature) and urine flow pattern in the kidney. The blood vessels are shown in red and the urine flow pattern in yellow.

Kidney - blood and urine flow

illustration

-

Glomerulus and nephron - illustration

The kidneys remove excess fluid and waste from your body. Blood is filtered in the kidneys through nephrons. Each nephron contains a network of small blood vessels, called glomerulus, which are enclosed in a sac called Bowman's capsule. The filtered waste product (urine) flows through tiny tubes and is then passed from the kidneys to the bladder through bigger tubes called ureters.

Glomerulus and nephron

illustration

-

Kidney stones - InDepth

(In-Depth)

-

Sickle cell disease - InDepth

(In-Depth)

-

Crohn disease - InDepth

(In-Depth)

-

Kidney stones

(Alt. Medicine)

-

Lyme disease and related tick-borne infections - InDepth

(In-Depth)

-

Viral hepatitis

(Alt. Medicine)

-

Coronary artery disease - InDepth

(In-Depth)

-

Atherosclerosis

(Alt. Medicine)

Review Date: 8/28/2023

Reviewed By: Walead Latif, MD, Nephrologist and Clinical Associate Professor, Rutgers Medical School, Newark, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.